The home of everything related to Twin Navion and Camair aircraft

- Home

- News

- Navion History

- Types of Navions

- Individual Aircraft Histories

- Database

- Stories

- Maintenance Resources

- Manufacturer's Brochures

- Publications

- Models

- Toys

- Collector Cards

- Flight Simulation

- Marketplace

- Links

In July 2008, Norman Cowell contacted me and informed me that I'd misspelt the name of Roger Keeney, owner of Acme Aircraft Co. He also informed me that Mr. Keeney

was alive and well in California. Using Mr. Cowell's information, I telephoned Mr. Keeney, now 97 1/2 years old, and got the real story of how the Twin Navion came

into being.

To learn a little more about this interesting man, read this short article marking his 96th birthday.

Roger Keeney celebrating his 96th birthday.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

Charles "Chuck" Daubenberger ran a manufacturing company called Dauby Equipment Co., Inc. with his brother. During World War 2, their business produced fasteners, clamps

and cables for the aviation industry under an agreement with Adel Fasteners. Following the war, Daubenberger earned his pilot's license and began purchasing a succession of

airplanes.

He also became involved with the Plastic and Rubber Product Co. (commonly referred to as PRP). A single engine Navion was purchased, and frequently flown to Montana where

McNeil Pearce (of PRP) had a lodge. He was unhappy with how the six-cylinder Continental engine would run while flying over the mountains, so he walked into the Acme

Aircraft Company in Lomita, California in search of a solution. Inside he found the man who would ultimately be responsible for bringing the Twin Navion to fruition.

Acme Aircraft's owner was Roger Keeney, a man who'd gone to work with the Douglas Aircraft Corp. in 1936 and spent the next decade working his way through various

manufacturing shops, and into the inspection department. "When the war was over, old man Douglas locked the door and said you guys are on your own," he remembered. Moving

from Santa Monica to Lomita, Keeney established Acme Aircraft as an FBO, doing piece meal maintenance work; converting Boeing Stearmans into crop dusters and looking after

local planes. When Chuck Daubenberger walked into the hangar with his Navion problem, a small 85hp pusher race plane was being constructed in the back corner. It would be

a fortuitous coincidence.

At first, Keeney talked with Daubenberger about the twins that were already available on the market - Beech C-45s and Douglas C-47s. Not only were they big, but Daubenberger

was put off by the $8,000 and $22,000 price tags. Keeney then suggested putting two engines on the Navion that he was already flying.

Keeney later recalled the initial brain-storm. I (jokingly) said, "See that round 55-gallon drum over there? We can get two of them and torch them out to fit over the wing

and attach them with a couple angles and some pop-rivets." Not only that, we could do it on a 337 Repair and Modification form. You could buy a new plane (from Ryan) and

sell the conversion and others wouldn't have to buy twins for $8,500." Daubenberger left the hangar with the idea planted in his mind.

That same idea continued to stir in Keeney's mind too, so turned to the man building the little air racer, Walter Fellers. Fellers was an aerodynamicist at North American

Aviation in nearby Los Angeles. "Let me look around at North American," he said. "In the meantime, don't do anything silly, like the barrel thing you were talking about."

Even though North American had sold off the production rights and all official information to Ryan Aeronautical several years earlier, many of the engineering staff still had

their hand-written working notes tucked away in their desks.

Keeney in the meantime approached the officials at his local Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) office. He and Fellers figured there was no reason that they couldn't approve

their work on a Major Modification or Repair form, commonly called the 337 form. The local CAA officials agreed, and Keeney reconfirmed this with an old friend of his,

Walter Johansson. Johansson had been the CAA official in charge of maintenance and manufacturing for the whole west coast. After their talk, he agreed to provide Keeney

with an official letter stating the 337 form would suffice.

When Daubenberger returned a couple days later, he brought with him two Navions, PRP's original and NC91793. "There it is," he proclaimed to a puzzled Keeney. "You said you

could make a twin, and I've got to keep the other one flying." It was April 1951.

Once they were sure the plan could work, a number of Douglas and North American engineers were brought into the project. Keeney later called them all, "good people." Walter

Feller served as the engineering lead and chief aerodynamicist, Will Bowman assisted with aerodynamics, Fred Anderson handled stresses, Ron Beatie performed tests in the

wind tunnel, and Malcom Oleson was a consulting engineer. After a short period of time, Daubenberger returned to see where his money was going. He wasn't happy to see that

nothing had been done to his plane. It took some explaining before he understood the work being done running numbers and checking to see if the airframe could even support

two engines. Working at night, they would pass their designs to Keeney, who would then have them approved in the morning at the local CAA office.

Then they'd start cutting metal.

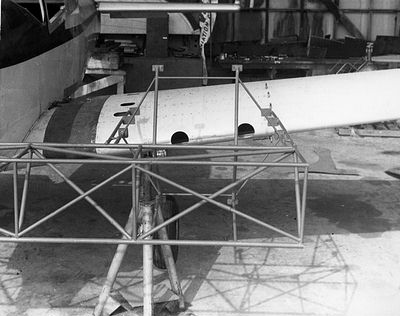

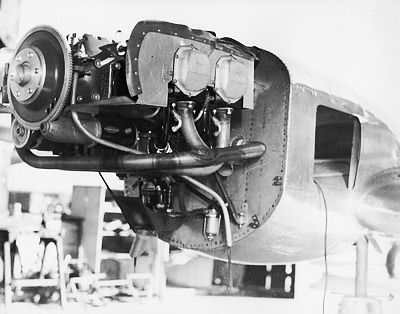

With the wing spar extended, the group began building the nacelles. But they needed an engine - quick. Keeney wrote to the big American engine manufacturers; Lycoming,

Continental, Franklin and Jacobs. Posting his message late in the week, Lycoming was the first to respond, on Monday morning. The representative was curious about what

they were doing, then told him, "there's no doubt you've got to put a Lycoming in it." The man on the phone sent drawings and offered to personally come to California and

help. The other manufacturers eventually replied. Continental wanted to know if the project was worth putting their engine on, while Franklin and Jacobs were going out of

business.

"Lycoming supported us the whole way through, that's why we used them," said Keeney. Because they felt it would be quicker and easier to work with an existing design, they

selected a four-cylinder, 125hp O-290-D and the engine mounts, accessories and cowlings from the Piper PA-18 Super Cub. Looking back at what effect the engine selection

process had, Keeney figured they could have raised the lower cowling by 4 inches. It was just part of working with the unknown. Had they used a Franklin engine those 4

inches would have been needed. Keeney also remembered that while they could have easily gone out and bought overhauled engines, Daubenberger insisted on brand-new ones.

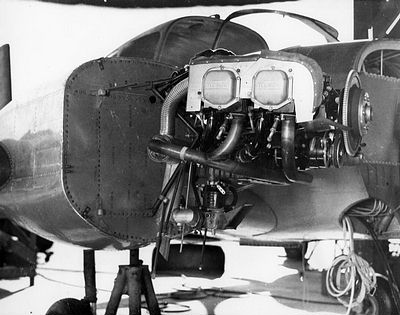

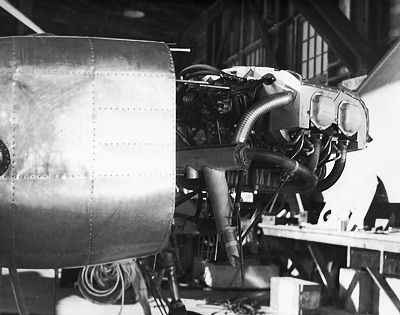

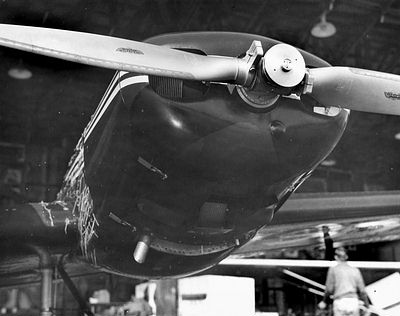

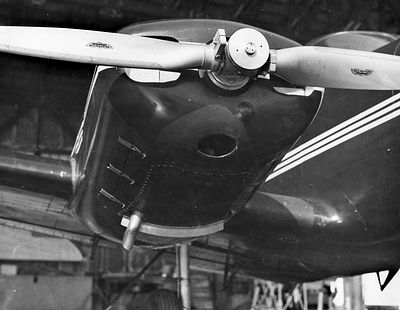

Various views of the construction of the engine nacelles, and the installation of the Lycoming O-290 engines.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

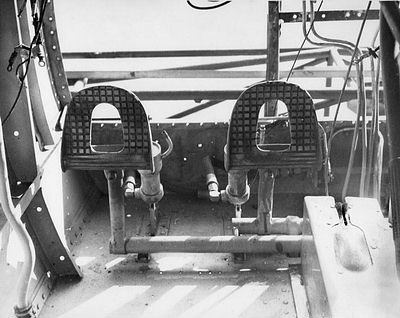

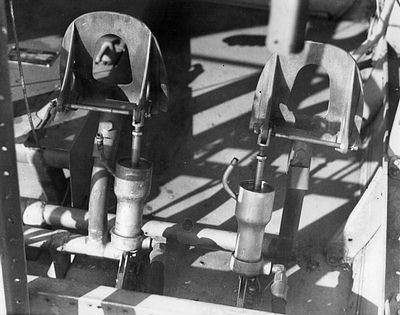

Details of the new rudder pedals with toe brakes, and the new panel-mounted throttle quadrant.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

The strive for quality later extended to refinishing the plane. It was stripped, polished and repainted in very dark blue and white. The interior was reupholstered in heavy

duty, suede leather.

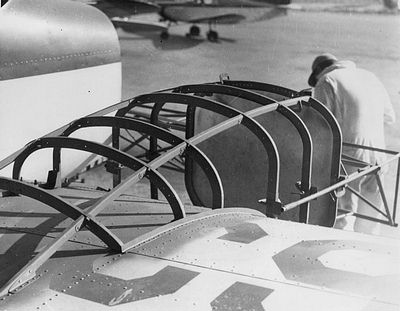

For simplicity sake, Keeney didn't bother redesigning the Navion's forward fuselage. Instead, he gave his sheet metal worker a simple order, "keep the wind out." The single

Navion's engine mount and firewall stayed tucked inside the original cowling, while the new nose cap was pounded out with a hammer and bag of sand.

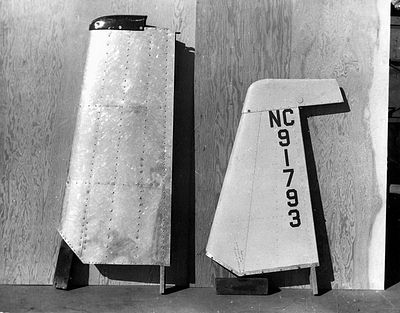

Several frame templates and the mockups used in making the first nose conversion. The large parts in the background are horizontal stabilizers from Douglas DC-3s.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

Attention shifted to the stabilizers and directional control. Even though the engineers told him the single Navion's vertical stabilizer and rudder were still large enough

to be effective, Daubenberger was a businessman and wanted to give customers something to justify the price of a conversion. "Engineering says we don't need anything back

there," he explained. "But how can I sell it?" As it happened, there was another Navion undergoing maintenance in the hangar, so they removed the horizontal stabilizer,

upended it, and held it against N91793. Daubenberger was happy with the look.

Side-by-side comparison of Navion and Twin Navion vertical stabilizers.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

The group also focused on correcting a number of issues the North American Aviation engineers had left. "Original Navions had issues with trim. They'd placed a wedge of

aluminum under the front spar to give it an angle of attack of 3-degrees." Feller's notes reminded him to remove the wedge. This later became a popular modification for

all Navions, called the Palo-Alto tail.

Eager to start testing, but knowing they'd still have to make changes, the group began taxiing, and then high-speed runs with the parts held together with temporary cleaco

clamps. After every run, they'd have to go back down the runway, picking up the dropped cleacos.

N91793 gets rolled out and parked beside PRP's single Navion.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

With the plane ready for flight testing, Jack Martin, Douglas' Chief Pilot was hired. He'd do all of the first test flights. Then Les Coan from the CAA would perform the

tests required for CAA certification. After the first flight Martin said simply, "This isn't a bad little airplane."

Soon Martin presented them with a challenge. "Just before you stall it, there's a little buffet. If you can fix it, okay. If not, I can still sell it to the CAA." Feller

came up with the idea of putting a large fillet between the trailing edge of the wing, and the fuselage. Keeney in the meantime had a couple Fairchild PT-19s that were being

scrapped because of their rotten wood. Taking the fillets off the PT-19s, they used tin snips to cut them to fit, and in about 30 minutes had solved Martinís problem. On

the next flight he reported it flying perfectly.

N91793, now painted dark blue, and two close ups showing the change in carbuerator scoops.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

Next was the dive to never exceed speed, which the CAA had set at 223mph. Martin flew the Twin Navion while Coan and Keeney followed in a Beech 18. Starting at 10,000 feet

they pushed over and started their full-power dive. When the airspeed reached 200mph Coan announced, "That's enough for this brittle wing bastard," and he aborted his dive.

Martin however continued to take the Twin Navion to 250mph, reporting it was "solid."

"There was still a song and dance going on about the single engine trim," explained Keeney. The CAA wanted the pilot to be able to take his hands off the controls with the

gear and flaps down, while only one engine was running at full power, and they aborted a test flight because of it. At the time, the rudder didn't have a trim tab and as

Keeney explained, "I'd lubricated all the ball bearings, so it really worked well. Had I left them alone, the friction would probably have made it okay."

Looking around the hangar, he found a screw jack with push-pull actuator, removed from a scrapped Consolidated BT-13 trainer. It was almost impossible to operate in the

very back of the tail, and since it was now midnight, Keeney elected to simply place the screw jack in the baggage compartment where it connected right to the rudder cables.

Reaching back from the pilot's seat, he could turn the crank and easily trim the rudder in either direction.

When the CAA arrived in the morning, they couldn't believe that Keeney had already fixed the problem. Coan didn't realize the solution was the small crank on the backseat.

Keeney sat in the back while the CAA pilots took off. They started by turning into the dead engine. Turning the crank brought the plane back straight ahead. Surprised,

because he wasn't expecting it, Coan had Keeney show him what he was doing. It didn't matter what engine was shut down, the salvaged BT-13 trim system could bring the plane

back on course. Afterwards, a trim tab was installed in the rudder and little by little, enlarged until it became effective.

Keeney later accompanied Coan to test the plane's spin recovery. "I don't want to get too much into this," Coan told Keeney, "but let's see what happens." Starting with the

landing gear and flaps down, Keeney was told, "as soon as it breaks, start them up, and start pumping (on the emergency hydraulic pump) like hell." It only went about 1/4 or

1/2 a turn before he had it arrested. He then said, "there's no use doing this to a twin," and the test was stopped. However Coan noted that there had been no movement in

the nacelles.

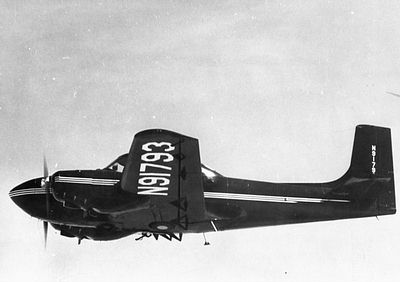

With the final pin-stripes applied, N991793 takes to the skies over California.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

John Martin was the group's test pilot, and Les Coan flew for the CAA, but Keeney performed some of the minor flight testing himself. On one flight to Long Beach, the

controllers in the tower asked him to give them a look. After flying past the control tower Keeney accepted their request for a closer look and landed. Ed Perillis, the

local CAA officer and a mechanic Keeney had known at Douglas, came down to look as well.

I asked, "Want to fly it?" said Keeney, and after a while Perillis enquired about his multi-engine rating.

"I told him I didn't have one," recalled Keeney. "I had a bunch of time in C-47s and T-50s, but no rating. I'd gotten my license back in 1930. I just never got my rating."

Marching into the CAA office, Perillis told the secretary to type up a multi-engine license - quickly.

On November 10, 1952, the CAA awarded the Twin Navion with its certification. The experimental X-16 became the D-16. Looking back, Keeney figured the name was derived from

Daubenberger's name and that is was the 16th plane he'd owned. While the certification was officially done by the CAA, the task once again fell to Keeney. When he called

the CAA to have them finish the approval, they promptly informed him that he was a delegate and he could therefore sign off his work. This puzzled Keeney, so he asked

another CAA official and received the same answer. At the very moment Keeney hung up the telephone, it rang, this time with Daubenberger. Once again, Daubenberger was

pushing to have his airplane finished. Keeney replied, "I told him to outside to the Santa Monica airport (his office was next door), and to look up. The airplane he

would see would be a fully licensed Twin Navion." After orbiting overhead for a few minutes, the air traffic controllers invited him to land, so they could see the new plane.

When he did, Daubenberger came running over wanting to see the paperwork. "When he saw my name on the papers he said 'Oh Jesus, we're in trouble.'" He calmed down after he

learned about the telephone calls.

Of course Daubenberger wanted to fly his new plane. He flew back to Torrance, where he dropped Keeney off, then proceeded to fly it for the rest of the day.

Soon afterwards an official in the CAA's engineering department contacted Keeney and forcefully informed him there was no way he would be allowed to sign off the Twin Navion

on a 337 form. During their telephone conversation Keeney asked if his work wasn't a major modification, and would it not be appropriate to use the Major Modification form

to justify it. The official's response was, "well the regulations aren't right, and we're changing them." He ended by threatening to prosecute Keeney and his company.

When Daubenberger found out about the conversation and of the letter from Walter Johansson, he smiled and took it to his lawyer.

Daubenberger and Keeney had every reason to be concerned. By this point, there was more than $16,000 invested in the plane they'd built. To recertify their work with a

completely new type certificate would easily cost ten times as much. A big meeting was arranged, and the CAA official took to strong-arming the Californians. Keeney

remembered their lawyer walking in a couple minutes after the meeting had started and literally forcing the man back into his chair. Johansson's letter was an official

document approving their course of actions. Just because the CAA wanted to change their regulations wasn't grounds to force people into following rules that had yet to be

written.

As testing was progressing on N91793, Jack Riley, a successful salesman became interested in the little Twin Navion. Thinking there could be a good market for the plane, he

arranged with Daubenberger to buy all of the rights to the design. A second Navion would be converted by Acme Aircraft. Riley's N91193 was rolled into the hangar and given

the most of the same modifications as Daubenberger's N91793. The biggest difference was the shape of the hand formed nose cone and the use of O-290-D2 engines. That change

yielded an extra 30hp. Daubenberger also figured that as part of the good will, Keeney should accompany him to Florida, where Riley Aircraft had their shop.

Once in Florida, Keeney remembers being met with open hostility from Riley's two English employees. "They were used to wartime quality control, which just meant getting it

finished," he explained. "They thought I was there to tell them how to run their show."

Instead, Riley sent Keeney and his test pilot, Peter Ethire, on a day long trip to the Florida Keys. While looking at the sights, Keeney spotted another Navion. It turned

out that it wasn't just another Navion, but the Navion prototype. Looking it over he noted numerous differences; the landing gear was interchangeable from left to right,

and the skins were substantially lighter. Later, Keeney asked Feller about this light weight Navion and discovered that while some components only needed 0.016 inch thick

material, North American Aviation had a surplus of heavier gauge sheet metal. Those thin parts were usually two or three times thicker than they needed to be. For a while

Keeney thought about buying the light weight Navion and converting it to a twin, until Feller explained that they'd counted a lot on the production Navion's thick skins to

support their conversion.

Sent to the Florida Keys, Keeney stumbled upon the light-weight Navion prototype, N(X)18928.

Photo courtesy of Roger Keeney

But Keeney still had concerns with the English Peterson brothers, since the first thing they did upon seeing N91793 was to start redesigning it. "I had the throttles in the

instrument panel, but they wanted them on the floor, between the seats, making it hard to get to your seat. They also wanted to start reshaping the nose. I pointed out that

the plane was certified to what we'd done, and left it at that." Later on, the CAA convinced Riley to recertify the Twin Navion under a new type certificate.

Addressing the lack of a feathering propeller for the Twin Navion, Riley contracted Hartzell to come to Florida and get a propeller certified. Using an oscilloscope to

measure the airframe's vibrations, they would slowly cut material away from the propeller tips, until the oscilloscope showed that it was running reasonably smooth. They

returned to the Hartzell factory and finished building the propeller. In January 1953 the HC 82 X-G-2 propeller was installed and certified.

With Riley Aircraft producing their slightly modified version of the D-16 in Florida, Daubenbeger and Keeney returned to California. Daubenberger continued to use N91793 as

a business plane for PRP. He eventually sold it to Jack Riley, were it was remanufactured to match their production D-16s. Acme Aircraft Co. became a large maintenance

facility, eventually working on equipping the underpowered Fairchild C-82 Packet with a Westinghouse J-30 jet engine, and certifying the Grumman F8F-2 Bearcat for civilian

use. When the Convair L-13 observation plane became available, Acme Aircraft certified them in the CAA's standard category after completing a long list of changes. It was

successful enough that three other companies tried to copy the design. Keeney also took a small number of Douglas B-18 bombers and strapped their bomb bays shut so they

could haul seafood out of Mexico. According to Keeney, those planes later hauled flowers from California to New York in the winter.