The home of everything related to Twin Navion and Camair aircraft

- Home

- News

- Navion History

- Types of Navions

- Individual Aircraft Histories

- Database

- Stories

- Maintenance Resources

- Manufacturer's Brochures

- Publications

- Models

- Toys

- Collector Cards

- Flight Simulation

- Marketplace

- Links

Photo courtesy of

Following World War 2, Jack M. Riley, a Texan, was in the blueprint business, which originated the use of the electric log reproduction

business. The logs provided a graphical recording of the location of an oil well's bore hole. He didn't actually invent the electric log,

but his salesmanship persuaded all of the oil drillers to give him copies of their individual logs. Riley put them together and produced

bore hole maps of huge areas; areas the size of states. Oil companies could now come to Riley and buy exact, scaled maps of oil

explorations. They came to him so fast that by 1952, he had 21 plants in the U.S. and a million dollar a year personal income. He retired

at 34 and moved to Ft. Lauderdale, FL to enjoy the good life. But something happened to Jack Riley in the oil fields, something that was to

alter the course of his life forever. He had bought his first airplane.

He says, "I bought it because I wanted it," but attributes a business growth from $100,000 a year to $3,000,000 a year within three years

largely to the airplane. What he doesn't say is that he also worked his butt off. The airplane left Riley on a permanent skyhook.

When he moved to Ft. Lauderdale, he could have bought some sleepy FBO and lived off the income from his electric logging business while

kidding himself that he was really in the airplane business. If you have ever met Jack Riley, you know that there was no chance of that

happening. Riley became the U.S. distributor for England's de Havilland aircraft and sold 19 Doves in 6 months. He was a one-man sales

force and single-handedly outsold the competitive Beechcraft twin. Beech, with its entire sales force and huge parts inventory, sold only 16

comparable airplanes. Riley's entire parts inventory was six spark plugs, an inner tube and a spare tire. What sold the Doves was not the

aircraft, but Jack Riley.

Riley and de Havilland parted ways, the British not being able to keep up with the high-flying Riley, or perhaps, as some suggest, they just

hated paying all that commission money out to him. In the end, the British lost, for after Riley's departure, Dove sales took a terminal

nosedive.

By now, Riley had decided that general aviation needed a true light twin, and so he built one. He decided that the single-engine Navion was

about the right size. It just needed twin engines. So, "I was too stupid to know that you couldn't make a twin out of a single," and he went

on and did it anyway. Riley knew exactly what would happen when he modified the Navion. Guys like Riley just don't gamble unless the odds

are all in their favor. And Jack Riley makes his own odds.

Says he, "You don't have to have any brains." Maybe not, but you have to have the guts to gamble big bucks when you hire top engineers and

draftsmen, build prototype parts, test everything and finally perfect a design good enough to qualify for a Supplemental Type Certificate.

Riley Aircraft Corporation, the located in Ft. Lauderdale, built 15 of the Navion twins before turning the design over to Temco. A

Dallas-based company that later became part of James Ling's LTV conglomerate. Riley went back into his log business and, on the side sold

all 85 of the Twin Navions that Temco built. He also opened up four more oil log plants. But Riley was hooked on the sky. He couldn't get

himself out of the airplane business.

Upgrading the Cessna 310 and 320 marked the beginning of a long association with Cessna.

Photo courtesy of AirNikon via Airliners.net

In 1959, he moved back to Ft. Lauderdale and began to build the Riley Rocket, a 250 kt conversion of Cessna's 310. Now you might wonder how

a guy like Riley, who had never built an airplane in his life, and operating out of a small facility at Ft. Lauderdale, got off building

something called a Riley Rocket. Riley figured that there were a lot of good components in the 310, but they just weren't assembled in the

right combinations. And about that time, he got thinking of Cessna as "my airframe manufacturer."

In 1964, the challenge was turbocharging, which today is the darling of the industry. When turbocharging was mostly a black art, Riley

brought in Rajay Corporation, manufacturers of turbochargers. Then he spent almost a million dollars perfecting the systems. All-in-all,

he developed and STC'd 19 turbo systems for general aviation aircraft, and also was OEM supplier of systems to Piper for the Twin Comanchee.

He probably had more influence in selling general aviation on the turbocharger than anyone else, and he takes credit for being the first

person to produce a general aviation airplane that would deliver 100% of its sea level power at 29,000 ft. After Riley developed the turbo

systems to his satisfaction, he sold Rajay and went on building customized, high-performance airplanes.

In 1963 and 1967, Riley upgraded the de Havilland Dove and Heron with IO-540s and the proved popular as business planes and commuter airliners into the

early 1980s.

Photo courtesy of Jerry Hughes via Airliners.net

Following a number of modifications to a variety of single-engine and twin-engine Cessnas, the Riley Aircraft Corporation went out of

business in 1983.

- Cessna 210

- Cessna 310

- Cessna 320

- Cessna 340

- Cessna 340A

- Cessna 337

- Cessna 414

- Cessna 414A

- Cessna 421C

- de Havilland DH-108 Dove

- de Havilland DH-114 Heron

- Hawker Siddley J.31 Jetstream

- North American and Ryan Navion

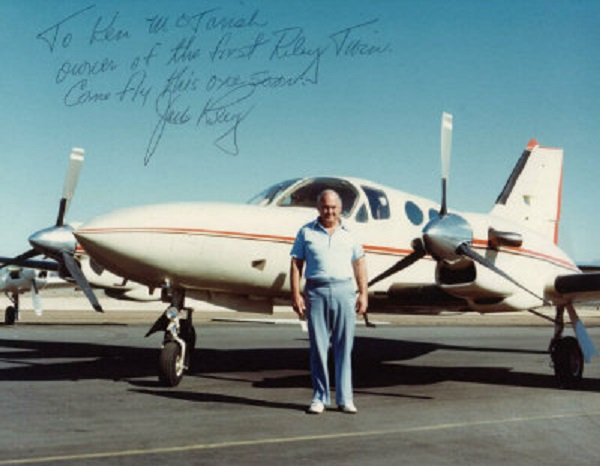

Ken McTavish's personalized photo of Jack Riley with one of the last planes he modified, a Riley Turbine Eagle, which was based on the Cessna 421C Golden

Eagle.

Photo courtesy of Jim Sundberg via Ken McTavish